- Home

- Bob Cashner

The FN FAL Battle Rifle Page 7

The FN FAL Battle Rifle Read online

Page 7

Hoare’s 5 Commando then conducted serious military training to weed out the undesirables and bring the unit together. Much of that training involved live-fire practice at a home-made rifle range with the new weapon issued to the mercenaries – the FN FAL rifle. Hoare himself was particularly impressed by the weapon and greatly appreciated the full-automatic capability for jungle warfare: ‘Every man who was armed with an FN rifle … was now the equivalent of a light machine-gunner, restricted only by the amount of ammunition he could carry or had immediate access to. With this firepower, four men with FN rifles were a potent force’ (Hoare 2008: 16).

As with just about everyone else who used the FAL, Hoare’s men found the weight of the weapon was an issue. It was impossible not to become weary carrying a 4.5kg (10lb) rifle all day and the regulation military sling could not keep the weapon in the ‘ready’ position. The mercenaries quickly figured out that the longer sling taken from the AK-47 could be jury-rigged into a useful assault sling – and the Simbas provided them with as many AK-47s as they could pick up off the ground.

Assaulted from the air and pushed from the ground, the Simbas in Stanleyville brought their civilian hostages out into the street and killed many of them literally within minutes of the arrival of the para-commandos. The liberated survivors were treated and flown out to the safety of the capital, Léopoldville (now Kinshasa).

Rhodesia

During the so-called Bush Wars in Rhodesia (1964–1979) the FN FAL was the favoured and most numerous weapon in the hands of the Rhodesian Security Forces. As with the counter-insurgency in Malaya, the Rhodesians took a ‘quality over quantity’ approach. In this case, they really had no other choice; the United Nations had embargoed the country. Thus, their heavy firepower was limited to some old 25-pdr artillery pieces, a few armoured cars and some generally obsolescent aircraft. Most of the Security Forces consisted of light infantry, and they were without a doubt the best light infantry in modern history; even the regular infantry formations could be considered elite. These included the Rhodesian Light Infantry, the King’s African Rifles, Gray’s Scouts and the Selous Scouts.

With the vast majority of actions being small-unit infantry engagements, the trooper’s rifle and his ability to use it became particularly important.

The standard small unit of the Security Forces was the stick, which consisted of four men: three riflemen armed with some version of the FAL, and one machine gunner carrying an FN MAG-58 machine gun.

Due to the international sanctions against the country, the Rhodesian 42

government gladly accepted any weapons they could get. They were

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

originally equipped with

British-made L1A1s. Later,

their FAL arsenal would

include the German G1

version and the South-

African-built R1.

As had the Malayan

ATOM manual (many of

those serving in Rhodesia

were indeed veterans of

the Malayan Emergency),

the Rhodesian Anti-

Terrorist Operations

(ATOPS) manual stressed

the need for the individual

soldier to deliver quick

and accurate rifle fire. One

of the ‘main requirements

for success’ was:

Snap shooting. The vital importance of accurate and quick shooting Rhodesian troops on operations

from all positions and all types of cover.

in the Bush Wars, 1968. The

The two most important training requirements are supreme physical Rhodesian security forces were

originally supplied with L1A1

fitness and the ability to shoot accurately at fleeting targets at short rifles, but after the Unilateral

and medium ranges. (Rhodesian Security Forces 1975: 35)

Declaration of Independence in

1965 only South Africa supplied

While many of the Rhodesian FALs, excluding the L1A1s, were capable arms – including the South African-made R1 select-fire FAL.

of full-automatic fire, semi-automatic was still generally favoured. Veteran (Photo by Monks/ Express/Getty and gun writer the late Dave Arnold explained why:

Images)

Like most of the Rhodesian Security Forces, the change lever on my FN was set for semi-auto only. I had the option of having this changed to include full auto, but I decided against it. Through practice, I could put down a devastating barrage of accurate semi-automatic fire that just could not be matched on full auto. I have never had much faith in full automatic fire capability in a full bore battle rifle, simply because you generally waste ammunition without hitting anything after the first shot has been fired. The recoil generated by the powerful 7.62mm NATO round makes the gun virtually impossible to control unless shots can be restricted to short two and three-round bursts. (Arnold 1987: 66)

A considerable number of H&K G3 battle rifles also found their way to the country, but these were used mostly by reserve and other non-frontline forces, while the men at the sharp end almost universally preferred the FAL. Although their ability to continually defeat opponents who greatly outnumbered them flew in the face of conventional military wisdom, it was not enough, and international political realities eventually caused the downfall of Rhodesia’s white minority regime.

43

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

44

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

45

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

The Bush Wars (previous pages)

When cover or ‘drake’ shooting during the late 1970s, Rhodesian riflemen were trained to shoot directly into and through the guerrillas’ position, keeping their aim deliberately low, while machine-gunners were required to aim at the ground immediately to the front of that cover. FAL

7.62×51mm NATO rounds have the power to punch through the tree trunks generally found in the African savanna and jesse bush, while the AK-47’s 7.62×39mm round generally did not. This fact was used to great effect by the Rhodesians, as tumbling rounds, dislodged stones, fragments of smashed rocks and splinters from trees could do great injury to those lying behind cover. The earth that MAGs kicked up would also force the enemy’s heads down.

The basic tactic was to draw the barrel of the rifle or machine gun across the covered position, usually beginning left to right, while squeezing the trigger at appropriate moments so as to ‘rake’ it from one side to the other. Each round or burst was fired in a deliberately aimed fashion. Experienced riflemen (when equipped with select-fire rifles such as the South African R1) sometimes used two-round, but no more than three-round, bursts on full-automatic when snap or cover shooting. Again, the first round was aimed deliberately low because the design and power of the FAL caused the barrel to rise rapidly on full-automatic. By aiming low, the shooter intended the first round to ‘skip’ and strike a prone target, while the second would go directly home as the barrel lifted.

South Africa

Of necessity, like those of Rhodesia, the SADF had to take a quality-over-quantity approach with their armed forces, creating some of the best light infantry in the world via tough, intensive training and two years of universal, mandatory military service. Many veterans of the Rhodesian Wars joined their ranks after Rhodesia became Zimbabwe in 1980.

Rhodesian police reservists

Technically, South Africa was at peace during the 1970s and 1980s, but undergo weapons training with

FN FALs, in the months before the

in effect the government was waging a seemingly endless counter-insurgency.

1979 election that ended the Bush

Nigeria, Angola and other countries sent guerrillas to attack inside the South Wars. Men aged between 50 and

African border, trained by Cuban troops and armed with the late

st Soviet 60 were called up to ensure order

Bloc military arms. As in Rhodesia, the FAL in well-trained hands proved in towns during the election.

(AFP/Getty Images)

superior to the AK-47 in poorly trained hands, and most actions were marked by relatively small groups of

South African soldiers inflicting

a disproportionately high

number of casualties on

numerically superior enemies.

Angola

The Portuguese also used the

FAL in their former colonies in

Africa. Even though their

standard infantry weapon upon

modernization became the

H&K G3 rifle, there were also

some Belgian-made FALs and

46

German G1 FALs in the

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

inventory. The FAL became the favoured weapon for elite counter-insurgency special-forces units such as the Caçadores Especiais (‘Special Hunters’).

THE ARAB–ISRAELI WARS

The FAL had first gone to war during the Suez Crisis of 1956 – a handful in British service as well as a small number serving with the IDF. The Israeli FAL, known as the Romat, would serve through both the 1967 Six-Day War and the 1973 Yom Kippur War as the IDF’s issue infantry rifle.

The FAL failed to make an impact in terms of public perception during the Arab–Israeli Wars; daring precision jet aircraft strikes and high-speed tank warfare across the open desert made the headlines. For the infantry in general and the paratroopers in particular, it was the famous Uzi submachine gun that possessed the ‘sex appeal’ to be most often seen in movies and photographs. The Uzi was at the time perhaps the best submachine gun in the world. Compact and reliable, with its 32-round magazine and cyclic rate of fire of 600rds/min, its firepower proved invaluable in the paratroops’ night assaults and in urban infantry battles.

In the desert, however, the Uzi’s 9×19mm Parabellum ammunition launched from a 260mm (10.23in) barrel quickly ran out of range and power. Ariel Sharon himself made note of this after the famous battle for the Mitla Pass during the 1956 Sinai campaign. Trying to fight their way out of an Egyptian ambush in the pass, his paratroops ‘… mounted the ridge and began to fight on it. When they reached the top of the ridge, the enemy opened strong fire with medium and light weapons from the …

ridge opposite, and from the caves. The [Israeli] unit was equipped in general with submachine guns [and] did not have weapons capable of returning the enemy fire’. (Luttwak & Horowitz 1975: 158).

For the Israeli Army, which had formerly been getting by with a variety of rifles from different sources and in different calibres, the Romat and the heavy-barrelled Makleon SAW would provide standardization on an unprecedented scale in the IDF, not only sharing a universal calibre, but magazines and parts as well. It would seem to have been a soldier’s and, even more so, a quartermaster’s dream come true.

The American military historian Brigadier General S.L.A. Marshall interviewed many Israelis shortly after the 1956 Suez/Sinai conflict and the Six-Day War of 1967, observing how the Israeli infantry operated, and how they incorporated all the weapons in their arsenal into their tactics.

He refers to the heavy-barrelled Makleon SAW as an LMG: Israel Army [ sic] is built up around an eight-man infantry section, the leader of which carries a submachine gun as does one other man. There are also two light machine guns with the section and four riflemen, one of whom is a specialist antitank grenadier.

In its attack formation during daylight, the section moves with the leader, the grenadier and one machine gunner forward as a three-man point. The others are deployed some paces to the rearward, two men on one flank, three on the other …

47

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

The Israeli heavy-barrelled

By Israeli training practice, when the light machine guns are used Makleon FAL with hinged

as a fire base to cover the forward movement of the rest of the section, buttplate. (Sapphire Gunsmithing/

they should not operate at more than two hundred yards’ maximum CC-BY-SA-3.0)

range from the target. To cut that distance by half is considered better.

In the attack LMGs are rated as highly expendable items and are shoved far front. When the section rushes the enemy position under cover of the LMG fire, one rifleman stays back to protect the gunners.

Rifle and LMG ammunition are interchangeable. There are sixty

magazines carried within the squad, twenty bullets to a clip, or twelve hundred rounds altogether. (Marshall 1958: 241)

The paratroopers were considered the elite of Israeli ground troops, and operated most often as light infantry. Operating out of range of supporting fire, often without air cover, and specializing in night assaults, the paratroopers fielded an eclectic mix of firepower to handle any situation: More than 50 percent of IsraeI's paratroops now have the Uzi submachine gun which is probably the best weapon of its type anywhere … At squad level, there are, at least three 7.62mm NATO rifles, usually two semiautomatic FN rifles and one similar weapon with a heavy barrel, a bipod and a fully automatic capability. One of the men equipped with a FN rifle generally has sniper training and sometimes a telescopic sight. All paratroops in Israel take pride in being able to shoot accurately themselves and most units have at least one real marksman. (Weller 1973: 49) The telescopic sight mentioned was, of course, the Israeli-manufactured version of the 4× SUIT. Users served more in the capacity of designated marksmen – less highly trained than real snipers, and operating within a squad rather than independently.

The IDF has long been fond of the rifle grenade. For night assaults on prepared defensive positions, Israeli infantry often crept to within rifle-grenade range. The assault was started with a volley of grenades onto the enemy positions intended to stun them and put their heads down, immediately followed by the infantry assault before their opponents could recover. In such assaults, close-range volume firepower from weapons 48

such as the Uzi was preferable to that offered by the Romat. As far back

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

IDF troops attack the Jordanian-

controlled West Bank village of

Samua, 1960s. Three soldiers

are armed with Uzis (the soldier

in the centre is reloading), while

their prone comrade has a

heavy-barrelled Makleon for light

support. (Cody Images)

as the 1960s, S.L.A. Marshall noted: ‘Israel’s infantry prefers the rifle-fired antitank grenade to the bazooka for shock effect on a group or bunker.

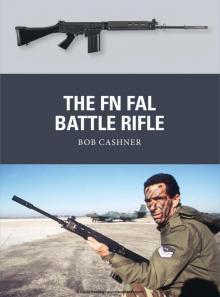

At night, if the section should run into an ambush, the grenadier fires and all the others rush straight in, not firing’. (Marshall 1958: 241) An Israeli soldier during the

At first, Israel manufactured a copy of the Energa rifle grenade for use Six-Day War, 1967. Although with their FALs. Other, more recent designs are still in production. A good much less celebrated as an example is the Israeli-made BT/AT 52. This is a BT rifle grenade that can Israeli service weapon than the be used from 5.56mm or 7.62mm weapons, which share the same-diameter Uzi submachine gun, the FN FAL

played a significant role in the

muzzle device, with a maximum range of 300m (328yd) from the latter.

Israeli infantry for two decades.

The Israeli doctrine of using tanks to kill tanks left the infantry ill- (© Henri Bureau/Sygma/Corbis) equipped with anti-tank weapons. One Israeli strongpoint

guarding the Golan Heights during the Syrian armoured

attacks there in 1973 had only a single bazooka and five

rockets for it. When these were expended, a young Israeli

lieutenant engaged five Soviet-made Syrian T-62 tanks with his Romat and rifle grenades, although doubtful of their

capabilities. He hit the first

two tanks and although there were no Hollywood-style fuel-air explosions, both tanks stopped

moving and stopped firing. The other three forced the

lieutenant back to the cover of the underground fortifications.

(Rabinovich 2004: 212)

Although much has been made about Egyptian use of AT-3

‘Sagger’ wire-guided anti-tank missiles, in 1973 Israeli armour also suffered heavily from the now ever-present RPG-7

shoulder-launched anti-tank missile. Well-camouflaged

Egyptian commandos, operating behind the lines, laid

ambushes along the routes taken by Israeli reinforcements and

fired large numbers of RPGs. When scattered by the surviving

tanks, they often regrouped in the dark and would lay another

ambush. Israeli tankers were also surprised by the regular

Egyptian infantryman of 1973; he was not the infantryman of

1967. The latter had often fled when Israeli tanks penetrated

their lines, but his successor held his ground against armour

and fired large numbers of RPGs. Only friendly infantry could

put them out of action for good.

49

© Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com

It was the IDF in the Sinai, much more so than UK troops in the Suez, who first encountered problems with the FAL in a desert environment.

Later, the story of the FAL experiencing extreme problems in the desert grew to become ‘common knowledge’ among the military and shooting community. Just how bad was the problem? It is hard to find actual after-action reports quantifying the malfunctions and jams in a desert environment. At one end of the spectrum Yisrael Galil (1923–95), who happened to build the Romat’s replacement, claimed to have seen piles of killed Israeli soldiers with jammed and useless FALs clenched in their hands. At the other end, American gun writers of the 1980s told horror stories (always second-hand, of course) of poorly trained Israeli reservists and conscripts tossing their FALs to the ground from the top of their vehicles and never bothering to clean them.

The FN FAL Battle Rifle

The FN FAL Battle Rifle